17/02/2024

17/02/2024

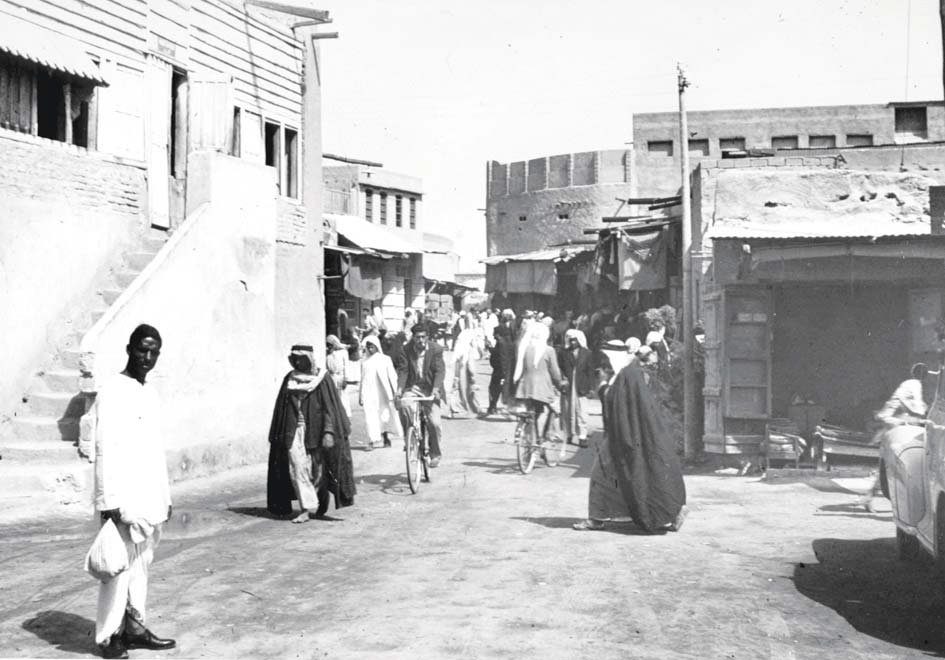

The sixties, seventies, and eighties were a time of renaissance in Kuwait. The sleepy, laid-back port town that had been chiefly dependent on trading, fishing, and pearl diving was reaping the benefits of the discovery of oil. In 1962, Al Sabah Hospital, the first grand hospital built by the Ministry of Health, opened. It treated patients from Kuwait and other countries in the Arabian Gulf. In 1966, Kuwait University, the first and oldest University in the Arabian Gulf, was established. Students from the Gulf region flocked to Kuwait to study under faculty members who held PhDs from some of the best universities in the world. Kuwait was home to some of the best literary magazines and published work in the region.

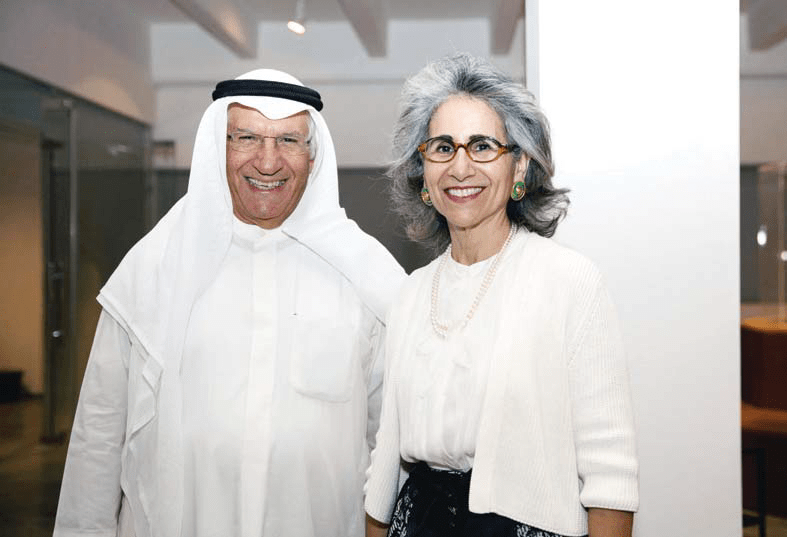

It became a center of literary and theatrical arts and scored high with a free press. Around this time, a similar renaissance was taking place in the built landscape of Kuwait. Among the Kuwaitis who led this renaissance was Sabah Mohammad Amin Al Rayes, a young Kuwaiti civil engineer who had recently graduated from Indiana Tech in the United States in 1965. Sabah Al Rayes is one of the first generations of Kuwaiti engineers who lived through the urban development of Kuwait. In the beginning, as an employee of the Ministry of Public Works and then as Founder of Pan Arab Consulting Engineers (PACE), a leading architectural consultancy, he contributed to the change that was taking place in the architectural narrative of Kuwait. Sabah Al Rayes is a man of many parts. Apart from being a pioneering civil engineer, he is passionate about arts and music.

A member of the steering committee of Dar Al Athar Al Islamiyah, he has played an important role in developing DAI’s music program. He is a legend to many Kuwaitis and architects who have worked under him or with him. Next week, Mr. Al Rayes will release ‘The History of Architecture and Engineering in Kuwait: A Story of a Homeland in Autobiography’ to the public. Published by That Salasil, a local publishing company, the book’s 800-plus pages explore not only the architectural heritage of the country but also comment on the socioeconomic history of Kuwait seen through the lens of an extraordinary Kuwaiti who experienced both the lows and highs.

Sabah Al Rayes grew up in Kuwait in the fifties, a time when the country was still a protectorate of the British Empire. He studied at Shuwaikh Secondary School, a leading public school of the time. “In those days, one had to choose between liberal arts and science. I chose science and specialized in mathematics,” he recalls. In those days, Kuwait was heavily invested in nation-building, and it was very important as part of the nation-building process that young people should be trained in fields the country needed most. Worthy students were selected for great scholarships. When asked why he chose to pursue civil engineering, Mr. Al Rayes smiles. “The government decided for me and my friends. After I graduated, the government decided that all students who had taken up science and math would do civil engineering.” In 1958, Sabah Al Rayes and thirteen young high school graduates found themselves on a flight to the United States. “We had a long stopover in London, which we reached after 24 hours,” he recalls. In those days, Al Rayes and his friends traveled in propeller planes with short breaks in Beirut, Athens, Rome and Paris.

“From London to the US, it took us another 24 hours. We flew from London to Glasgow and then to Newfoundland before reaching New York after another 24 hours.” For 17-year-old Al Rayes, who had never been out of Kuwait, it was quite an experience. “In Kuwait, the highest building then had two floors. Seeing those tall buildings in London and New York was quite an experience. Then, we encountered elevators for the first time. You enter this little box, and it takes you up and down. It was all quite fascinating.” Al Rayes can still remember the excitement of being at Times Square during his first New Year celebrations in the States. “It was amazing,” he smiles. What was Kuwait like when he was growing up? It must have been very different from what is today. “It was a beautiful pedestrian city,” recalls the civil engineer. “Everyone walked. My grandfather, my father, and my friends – all walked. You could walk from one side to the other. There were less than 800 vehicles in the total area of Kuwait in 1957.” As far as the built landscape was concerned, most buildings were adobe, a combination of mud and hay. Mr. Al Rayes’s new book, “History of Architecture and Engineering in Kuwait’ discusses the traditional architecture of Kuwait in detail. “Adobe buildings provided good insulation, but the problem was it eroded in rain. Before the rains, people would start plastering buildings and preparing for the season. In the early thirties, we had terrible rains and most buildings in Kuwait were ruined. The same thing happened in 1954. Adobe buildings were not sustainable. They required continuous maintenance.” Interestingly, in the mid-twentieth century, 35 % of Kuwait lived in one-room adobe houses. Only two percent of the people lived in big homes with multiple rooms. Mr. Al Rayes stayed abroad until 1965. By the time he returned, Kuwait had gained its independence.

The architectural landscape of the country had changed. According to him, it was the first master plan by British planners Minoprio, Spencely& Macfarlane in 1951 that defined the road map for urban development in Kuwait. By the time Al Rayes came back, Kuwait had changed. “By 1961, the first five-story building with central air conditioning and elevators was built in Kuwait. Two buildings were five-storied. One of them is now occupied by the National Council for Culture, Art, and Letters, and the other is the Kuwait Municipality building. The roads were upgraded. From 8,000 cars in 1957 to 800,000 cars in 1965. It was a big change in a short time.” After returning to Kuwait, Mr. Al Rayes joined the Ministry of Public Works for three years. “We were seven engineers that controlled the development taking place in Kuwait,” he recalls. “, I think we could have done much better. We could have stopped this slaughter of pedestrian space.” In 1968, Mr. Al Rayes resigned from the Ministry and founded The Pan Arab Consulting Engineers (PACE), which not only became a leading architectural consultancy in the region but, along with other Kuwaiti consultancies, took part in the urban development of Kuwait. Mr. Al Rayes believes that in its quest for modernization, Kuwait lost its old-world charm.

Modernization

“Unfortunately, this is the price we paid for modernization. We got rid of what the West is trying to develop in their cities. They want pedestrian cities while we demolish what we have. Unfortunately, this is still going on.” Kuwait saw an urban renaissance in the seventies and eighties, as it evolved from a society dependent on trade and pearl diving to a society driven by oil. In 1946, after oil started being shipped, the foundation stone of Ahmadi was laid. The town of Ahmadi was built from scratch in the desert where roads were laid.

On the other hand, Kuwait City had the infrastructure, but it was not adequate. “The main buildings of Ahmadi were airconditioned with running water and a sewage treatment plant. We built a whole city, with the houses prefab from Europe. Ahmadi was built as a British countryside village. We used to visit Ahmadi to admire the buildings and the landscaping. The development in Ahmadi took a completely different course than the development of Kuwait City.” Speaking of the story behind his new book ‘The History of Architecture and Engineering in Kuwait’, Sabah Al Rayes said, “As a person in the profession, I started reading to learn more about the past, and I was shocked to find out there were no books except for two. One of them was by Dr. Saba George Shiber, a wonderful planner who documented many things. He came to Kuwait in 1960 and passed away in 1968 at the age of 45. He contributed so much to the development of Kuwait. He reviewed the master plan of 1952.

I failed to find something else that was more detailed, and that’s what drove me to write my first book in Arabic about the history of architecture and engineering in Kuwait.” Although the new release shares the same title as the Arabic one, it is not a mere translation. “I have added a lot to it. This is a different book that targets expatriates,” he urged. In his book, Mr. Al Rayes speaks at length about old Kuwait. When asked about life then and if Kuwaitis of the past were more resilient, he said, “ I disagree with many people from my generation who speak of the good old days. There were no good days. There was a lot of suffering. There were times my mother sent me to get the donkey boy to bring water.

There were eight children in the house, and we didn’t have enough water. Those days were tough. And we were considered middle-income, above-average people. So, imagine the plight of the poor people.” The tome, whose cover page features the Khaleejia building, the first twenty-storied building in Kuwait that Sabah Al Rayes designed, addresses the lack of reference to the development of the built landscape in Kuwait. From an in-depth historical overview, the book, which took six years to be published, takes us through the old city, the fascinating three walls built to protect the city, the socio-cultural context, the housing policy, accommodations, the master plans, distinctive buildings in Kuwait’s past, Ahmadi, the reign of Sheikh Abdullah Al Salem Al Sabah, infrastructure, occupation of Kuwait and the liberation of Kuwait.

The British were strongly involved in the first and second master plans. “The British were involved in everything,” says Mr. Al Rayes. “From 1946 until independence, they were involved in everything. They were economic, architectural, and engineering advisors to the Ministry of Public Works. The group that did the first master plan did a fantastic job defining and designing the city of Kuwait with a string of roads. They set the roadmap for any development. The master plan saved us a lot of the chaos that took place in other countries that did not follow a master plan,” he said. As Kuwait underwent an urban renaissance, it did away with several vestiges of the past. “Civilization is half destruction,” he says. “At that time, people wanted to eliminate anything that had to do with the past. They did not want to remember the misery we lived in.” But Sabah Al Rayes is glad about the awareness and resistance of Kuwaitis to the recent plan to get rid of iconic structures like the Bayt Lothan or the Ice-Skating rink. “I am 85 years old. I have done many things that I am very proud of and satisfied with. All the buildings I designed or was very much involved with became iconic buildings.” What about the urban landscape now? Are they environmentally sustainable? “No. Unfortunately, because of the cheap cost of fuel and energy, this part is truly neglected. Even though people talk about smart buildings or talk about the environment, I see little on the ground.” The History of Architecture and Engineering in Kuwait is available in That Salasil.

By Chaitali B. Roy

Special to the Arab Times