14/10/2025

14/10/2025

Drawing a sketch of ‘the historic Kuwaiti mosque’ is not easy. The reason for this is the lack of documentation and available information. What is surprising is that, despite the very young age of mosques in Kuwait (the oldest of these historic mosques dates back no more than two centuries), there is hardly any information available. Much older mosques and buildings in other parts of the world are far better documented.

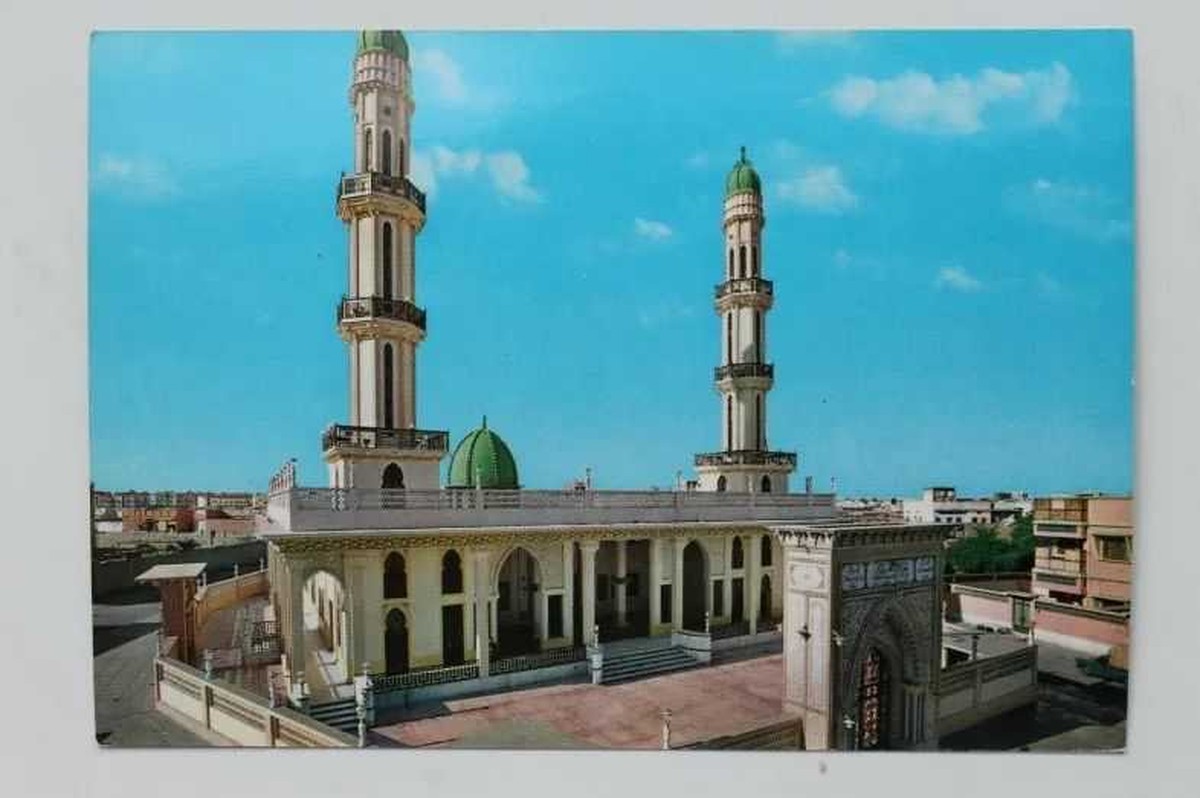

The Al Othman Mosque in Hawally, located on Al Othman Street, was built in 1958 by Abdullah Abdul Latif Al Othman (1897–1965), a pioneering Kuwaiti businessman and philanthropist. Al Othman, who also founded the Al Othman School, one of Kuwait’s earliest modern private schools, played a key role in shaping the country’s educational and cultural landscape. The mosque itself is among Kuwait’s first modern grand mosques, serving as a landmark of faith and community life.

Today, a partnership between the Abdullah Al Othman estate and Kuwait’s National Council for Culture, Arts, and Letters is working to revitalise both the Bait Al Othman Museum and the Al Othman Mosque, with the goal of enhancing their roles as vibrant centres for religious, cultural and creative engagement.

I recently visited the Al Othman Mosque, where I met Zahra Ali Baba, a Cultural Heritage specialist with the National Council for Culture, Arts and Letters and the Co-founder of Heritage Workers, a non-profit organisation dedicated to heritage advocacy and conservation. The meeting was facilitated by Ksenia Graovac, a culturologist and manager of the Promenade Culture Centre.Deeply involved in community building through art and culture, Ksenia is also one of the driving forces behind the restoration of the Al Othman Mosque.

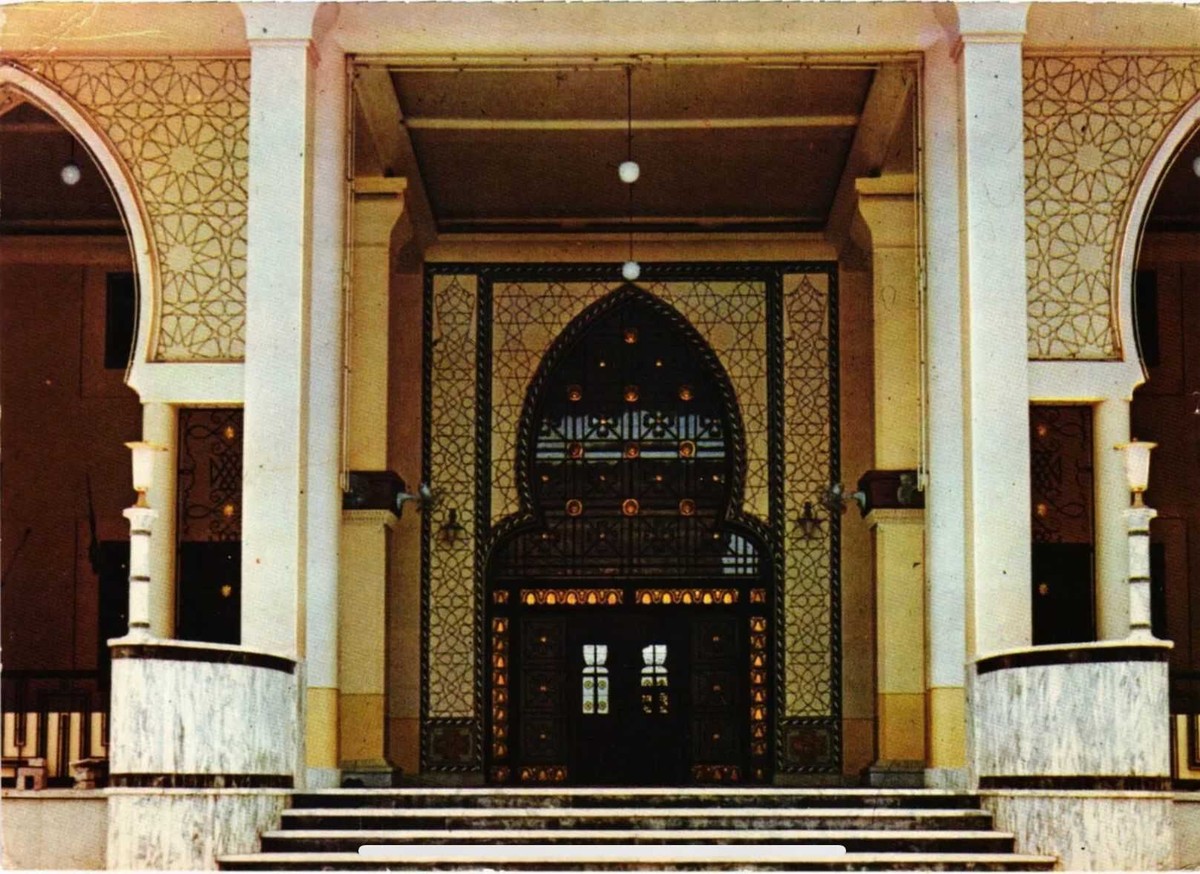

Our discussion centred on the restoration and historical features of the Al Othman Mosque in Kuwait. We discussed the use of mosaic, concrete, and terrazzo, as well as the discovery of a large mural that had been painted white and later uncovered. Restoration efforts involve preserving original elements, such as columns and tiles, and removing modern additions, including false ceilings and Moroccan features. Notably, the Al Othman Mosque holds the distinction of being the first domed mosque in Kuwait and one of the earliest to incorporate modernist design elements in its doors and windows.

The restoration aims to showcase the mosque's diverse architectural influences. “There were a couple of restoration attempts in the past, if you can call them that,” shares Ksenia. “During one such attempt, it changed colour from green to white. We discovered incredible colours, beautiful murals under the white paint, and we are trying to honour as many heritage features as possible.”

What makes the Al Othman Mosque architecturally unique is that it is built and decorated in a variety of Islamic styles. What is also interesting is the time at which it was built. The 1950s and 1960s were a time of growth and urban renaissance in Kuwait, during which most of the country’s first modern buildings were constructed. Apart from serving as a community hub for religious and cultural values, the mosque, which features an eclectic mix of styles including Islamic, Tuscan, Victorian, modern, and Art Deco, is a notable example of this renaissance and a stellar modern Kuwaiti building.

Speaking of the importance of the building, Zahra Ali Baba notes, “It tells you about a very special moment in time in the evolution of mosque architecture. This is considered one of the earliest mosques to be built outside the third wall – the Othman Mosque and the one in Ahmadi - and they represent completely different approaches to conceptualising a modern mosque.”

Explaining the contrast between the two contemporary mosques in Hawalli and Ahmadi, Zahra noted, “The Ahmadi Mosque was designed by Wilson Mason architects, who were active across the Northern Gulf, in Basra, Khoramshahr, and Abadan-building for the oil industry. At the time, with the Ottomans being pushed out, there was resistance to the British presence. To ease tensions, the architects cleverly used local materials and incorporated regional shapes and features, ensuring the buildings felt familiar and rooted in the local environment. It was their way of showing that these structures were built for the people, not as symbols of colonial occupation.”

What makes the Al Othman Mosque singularly interesting is that it is one of the first mosques in Kuwait to have a dome. Previous mosque constructions in Kuwait featured a flat roof, in keeping with the traditional Arabian Gulf architectural vocabulary. “The dome is a Christian feature,” explained Zahra. “The Prophet's mosque (PBUH) did not have a dome. Additionally, the construction technique was not in place.”

Mosques are among the most important Islamic buildings, characterised by unique features. Functionally, it is a place of worship, socially, it is a place of gathering and discussion, aesthetically, it is an architectural object that possesses beauty and inspires creativity. “ The most important feature of a mosque in this region is a courtyard where people congregate. It is pluralistic and a common simple feature of Gulf architecture,” says Zahra. When asked about minarets, she says, “The minarets were traditionally very short; they did not have the structural capacities to build taller structures. In the early 1930s and late 40s, when construction workers migrated from Iran, they introduced taller minarets with elaborate decorations.”

From an Islamic point of view, Muslims believe that building, caring for and maintaining mosques is the best act of worship. In 1904, there were between twenty and thirty mosques within the walls of Kuwait, four of which a number were major congregational mosques (holding Friday prayers). The rest were smaller mosques in the different neighbourhoods. It is worth noting that the great majority of mosques were built by wealthy individuals, whose families, in many cases, took pride in maintaining them. Abdullah Abdul Latif Al Othman, who had already embraced philanthropy as his life’s calling, built several mosques in Kuwait and Lebanon. Al Othman had an interesting life. He transitioned from a student to a teacher, then a pearl diver, merchant, and eventually into a landlord. He built numerous mosques in Syria and Lebanon and supported various philanthropic causes worldwide. Despite facing bankruptcy, he rebounded by entering real estate, creating a market that reduced buyers' risk. His generosity and vision for Kuwait's development are exemplary, including his efforts to preserve historical buildings and his contributions to the community. “He was one of the kindest men,” recalls Adnan Al Othman, Abdullah Al Othman’s son and the force behind the strengthening of the Al Othman legacy. “He did not care about how much he spent. He never cared about how much wealth he had. And he was so very generous. He donated around the world, in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and as far away as Argentina. We are just trying to save some of that legacy for the future.” When asked how he navigates the very difficult landscape of bureaucracy in Kuwait, which sometimes can become an impediment in such projects, he smiles, “I know it takes time. I have my own way. I know how to negotiate. I knock the doors the right way, the legal way, the polite way.”

“We are constantly discovering the beautiful colours and the patterns on the mosque,” observes Ksenia as we make our way through the restoration efforts gingerly. “This mural was completely covered,” she said, pointing out to beautiful patterns emerging on one of the walls. “ We have uncovered it all. I recall receiving a small block that the engineer sent over to me. I cried a little. Imagine what it must have looked like in its original form! We literally found it by chance, and we are being very careful with what’s behind the white paint.”

Restoring a historic building involves striking a balance between preserving its cultural authenticity and incorporating modern functionality, prioritising repair over replacement, and adhering to strict building codes and regulations. The overall goal is to preserve the building's character and history while adapting it to meet contemporary needs. The team supervising the restoration of the Al Othman mosque is doing just that. “There was a false ceiling here,” said Ksenia, pointing out as we stood in the prayer hall. “We needed to be very careful with bringing back the original proportions of the mosque, the slender columns, the materials underneath. We have also restored some of the old tiles that we could, and some are new.” The presence of meticulously maintained records and videos from the opening ceremony has provided the team with guidance on how the restoration will be carried out.

In the 2000s, Moroccan decorative elements in mosques in Kuwait became popular, and the Al Othman mosque was no exception. “ This restoration is also important because it highlights the variety of attitudes prevalent at a time,” observes Ksenia.

The Al Othman Mosque was a modern mosque when it was built. In a way, it symbolised a modern and more developed Kuwait. “In this mosque, there was freedom to be more creative,” says Zahra. The result is a very eclectic mix of influences, including Hellenistic elements, modern abstract art, metalwork, and the use of colour. “ The use of colours in this mosque is extraordinary,” observes Zahra. “Earlier, everything was sand washed, it was as if Kuwait was colourblind. To build a religious building that is so colourful is interesting.”